Editor’s Note: This blog post is a part of a new ongoing series of posts dedicated to K-12 education policy in Mississippi.

***

By Grace Breazeale I K-12 Policy Associate

A growing student debt crisis may be contributing to Mississippi’s critical teacher shortage. Mississippi First’s 2022 Teacher Survey, completed by 6,496 teachers across Mississippi, provides clues about the severity of this crisis, as well as its apparent impact. Of all teachers surveyed, 23.5% owe at least $50,000 in student loans, and 10.6% owe at least $100,000–amounts that are far beyond what most teachers bring home in a given year. Our findings are reinforced by other research: a 2020 NEA survey found that educators with a student loan balance owed an average of $58,700. One in seven still owed at least $105,000.

These striking levels of debt have tangible implications for individuals themselves as well as for the future of the teaching profession. For individual teachers, excessive student debt becomes interconnected with a teacher’s overall financial well-being. The teachers in our survey who currently hold student debt are

On a systems-level, the amount of debt that teachers hold could be contributing to teachers leaving the classroom for better-paying careers, exacerbating teacher shortages in districts across Mississippi. Compared to teachers in our survey with no student debt, teachers who hold student debt were nearly 10 percentage points more likely to report that they are likely to leave the classroom within the next year (based on when the survey was administered, this would be by the end of 2022).

A major issue contributing to the student debt crisis—a crisis that is not confined to teachers alone—is the complexity of the student loan system, which is notoriously opaque. When researching the topic, one can find an abundance of conflicting information on almost every aspect of student loans from the structure of interest rates to the terms of loan forgiveness programs. Loan servicers themselves have even deceived students about the terms of loans.

In this post, we seek to cut through this conflicting information to provide a clear description of the student debt crisis among teachers in Mississippi and paths available to teachers that could lessen the financial burden posed by their student debt.

Why are future teachers taking on so much student debt?

The sheer number of teachers who hold large amounts of student debt makes it clear that the problem is systemic, and it’s worth examining the context of the system that has created this issue. Unsurprisingly, a large contributor to student loans is the rising cost of college tuition over the past several decades. State investments, which are a large source of revenue for public universities, have steadily fallen, forcing universities to compensate by raising tuition. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports that state funding per student fell by a full 34% in Mississippi from 2008 to 2019. The average cost of attending a four-year public university in the state during the 2008-2009 school year, including tuition, room, and board, was $15,159; during the 2019-2020 school year, the cost was $19,918 (both figures adjusted for inflation). Over the course of 11 years, the cost of attending college for one year rose by nearly $5,000. While federal and state-specific grant programs exist to help students fund their degrees, the majority of these programs have not expanded or increased at the same pace as rising tuition, meaning they cover a smaller fraction than in the past. This leaves many prospective teachers (and college students generally) with no choice but to take out substantial student loans.

What types of loans are available to student borrowers?

There are two primary types of loans available to student borrowers: federal and private. The following table outlines characteristics of each type.

| Federal Loans | Private Loans |

|---|---|

| Fixed interest rates | May have fixed interest rates or fluctuating interest rates |

| Generally have low interest rates (4.99% for new undergraduate loans)* | Generally have higher interest rates than federal loans |

| May be subsidized or unsubsidized (subsidized loans do not accumulate interest while a student is in college or during a six-month “grace period” after graduation) | Are generally unsubsidized (interest begins to accumulate immediately) |

| Have limits on the amount that can be taken out:* Limit of $31,000 for dependent undergraduate students (borrowers who depend on their parents’ income) Limit of $57,500 for independent undergraduate students (borrowers who meet one or more of the criteria laid out by the Department of Education) Limit of $138,500 for graduate students (including undergraduate loans) | Usually allow a student to take out loans up to the cost of attendance for their school (can be contingent on student’s credit history) |

| Offer opportunities for loan deferment or forbearance in which a borrower can apply to have their loan payments paused for a short period of time | Generally do not offer opportunities for loan deferment or forbearance |

| Offer opportunities for loan forgiveness, such as the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (described in more detail below) | Generally do not offer opportunities for loan forgiveness |

A borrower can take out either or both types of loans to fund their degree(s). If students reach the cap on subsidized and unsubsidized federal loans and need additional help to meet their college’s cost of attendance, they have several choices. One option is for the student to use Federal Direct PLUS loans. The parents or guardians of undergraduates can take out these loans for their children, and graduate students can take them out for themselves. However, the interest rates on these loans are higher than on typical undergraduate federal loans. The other option that students have is to take out private loans up to the cost of attendance. The vast majority (nearly 93%) of student debt is held in federal loans, which generally offer more amenable terms to borrowers than private loans.

The Role of Interest

The structure of interest on student loan debt can contribute to the difficulty of escaping the debt spiral. Interest on student loan debt accumulates daily, rather than monthly or annually.

Finding Interest Amount That Accumulates Daily

To find the amount of interest that accumulates daily, a borrower can divide their interest rate by 365, then multiply this by the principal amount of the loan (the remaining balance owed).

An example is below for a borrower who has a loan principal of $15,000 and an annual interest rate of 5%.

Daily Interest Rate: 0.05/365 = 0.00014

Daily Interest: 0.00014 x $15,000 = $2.05

This borrower accumulates $2.05 of interest each day. All federal and most private student loans use simple interest, which means that the amount of daily interest is not added to the principal amount of the loan.1 If the borrower in the example has a simple interest loan, they would owe $61.50 ($2.05 x 30) of interest in a 30-day month. Typically, their monthly loan payment would cover the full amount of this interest, in addition to paying down the loan principal. Thus, people who have student loans with simple interest generally see the principal amount of their loan decrease over time.

There are, however, a number of situations in which interest may be added to the principal amount of a simple interest loan, which is called capitalization. In these cases, the borrower must pay interest on the loan’s interest. Let’s examine situations in which this could occur.

Situation 1: Enrollment in School/Grace Period

Unsubsidized federal loans, as well as private loans, begin accumulating interest the moment they are disbursed. Students are typically given until six months after they graduate college to begin making payments on these; however, if a student does not make payments while they are in school or during the six-month grace period, the interest that accumulates is added to the principal amount of the loan once they start making payments. Thus, the student will end up paying interest on this interest. Note that interest does not accumulate on subsidized loans while the borrower is in school or during the six-month grace period.

Situation 2: Forbearance or Deferment

Students can request forbearance or deferment on their student loans for a variety of reasons, including (but not limited to) financial hardship, enrollment in college or career school, or active duty service. Generally, forbearances are granted for one year and deferments are granted for up to three years. In most cases of forbearance and deferment, the borrower is not required to make their monthly payments, but interest still accumulates. If the borrower does not make payments that cover the amount of the interest during this time, it is typically added to the principal balance of the loan (capitalized) once their payments resume.

Situation 3: Income-Driven Repayment Plans (in certain cases)

Under an income-driven repayment plan, a borrower’s monthly payment is based on their discretionary income. The payments on these plans are lower than payments on a standard repayment plan; in some cases, the payments are not large enough to cover the full amount of one’s monthly interest. For most income-driven repayment plans, the remaining interest beyond the amount of the monthly payment is covered by the government. However, under some plans, the remaining interest is added onto the principal amount of the loan. Income-driven repayment plans are described in greater detail in a later section.

Accumulation of Debt

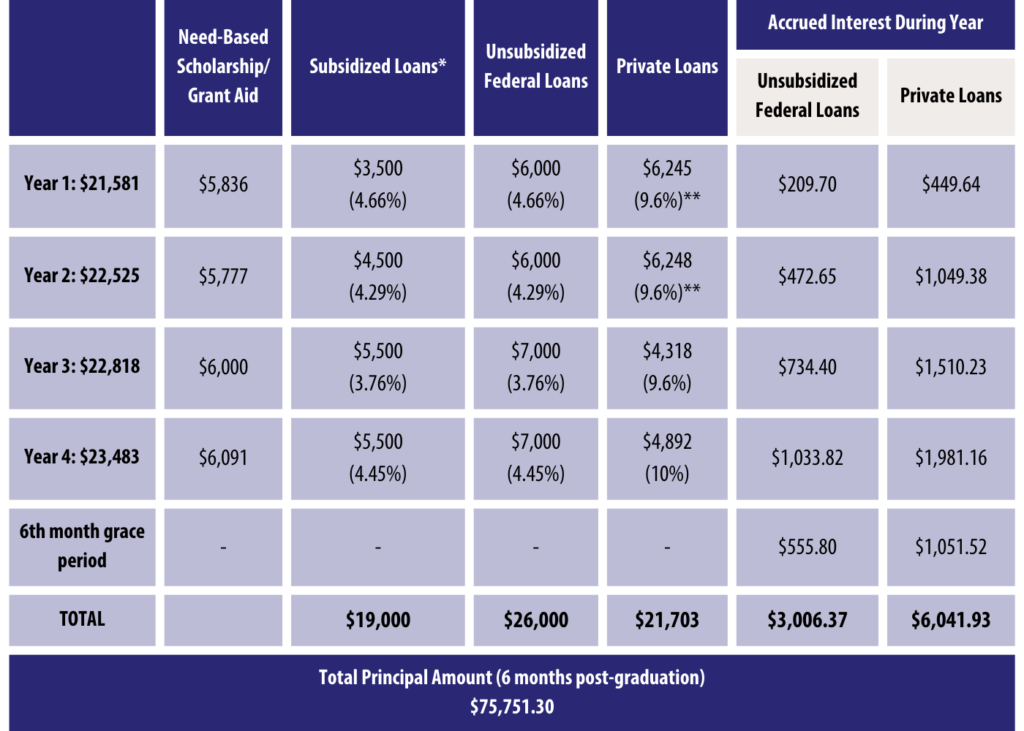

Given the above information, we will now examine a scenario in which a teacher in Mississippi could accumulate tens of thousands of dollars in student debt. Let’s consider a hypothetical teacher who attended one of the state’s largest public universities, Mississippi State University, from 2014 until 2018. During the 2014-2015 school year, the average cost of attending MSU was estimated to be $21,581 for an undergraduate, including tuition, housing, transportation, books and supplies, and other fees. In total, an undergraduate who was a freshman in 2014 would pay an estimated $90,407 over the course of four years, accounting for annual tuition increases. The student in our example was considered independent from her parents when she applied for student loans. She took out the maximum amount of federal student loans, received MSU’s average amount of need-based grant and scholarship aid, and took out fixed-rate private loans to cover remaining costs each year. The chart below demonstrates how the principal amount of her loans could have grown to over $75,000 by the time she reached the end of her six-month grace period after graduation. Note that the capitalized interest from unsubsidized federal loans and private loans has already added over $9,000 onto the principal amount of her loans.

**Average private loan interest rates are unavailable for the 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 school years; for these years, we assume the same average interest rates as the 2016-2017 school year. These are likely a slight underestimate, based on the trend for federal interest rates.

If this borrower was on standard repayment plans, her monthly student loan payment would be $492 for her federal loans and $362 for her private loans. In total, her loan payments would amount to $854 per month. She would ultimately pay $102,481 over the course of the 10-year repayment plan with an annual salary that does not top $50,000 over the course of the decade. If the borrower decided to go back to school to get a graduate degree–which is not unusual for teachers–her debt figures and monthly loan payments would likely be even higher.

Options for Teachers with Debt

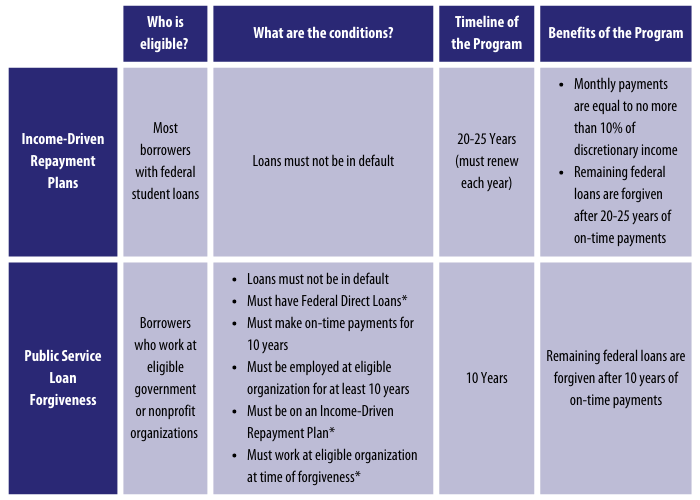

Despite the severity of the student debt crisis, teachers in Mississippi have opportunities to mitigate this financial burden–perhaps even more than they may be aware of. At the forefront of these options are income-driven repayment plans, of which there are several different types. Under income-driven repayment plans, an individual’s monthly payment is based on their salary, and the value of their payment is typically no more than 10% of their discretionary income. In our example above, the borrower had a monthly payment of almost $500 for her federal loans. On an income-driven plan, her monthly payments for these loans would be around $200 during her first year of teaching (over time, it would increase proportional to her salary). An additional advantage of income-driven repayment plans is that the government forgives any remaining debt after 20 years of on-time payments (25 years for some plans), so some borrowers end up saving money, depending on their initial level of debt. (We recognize that paying student loans for 20 years is a really long time!)

While lower payments mean a longer repayment period as well as a higher accumulation of interest, Income-driven repayment plans can be a useful option for borrowers with high monthly loan payments. Considering the proportion of teachers with loans in our survey who report that they struggle to make their monthly payments (over 70%), these repayment plans may be underutilized among teachers. Only 36.4% of teachers with debt above $50,000 and only 40.7% of teachers with debt above $100,000 report that they participate in this type of program.

In addition to income-driven repayment plans, teachers are eligible to participate in the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program (PSLF). Under this program, individuals who are employed by the government or a qualifying nonprofit organization can receive loan forgiveness after making 10 years of on-time monthly payments (for a total of 120 payments) on their qualifying federal student loans. Participants in this program must be on an Income-Driven Repayment Plan and must be working for a qualifying employer at the time in which they receive loan forgiveness.*

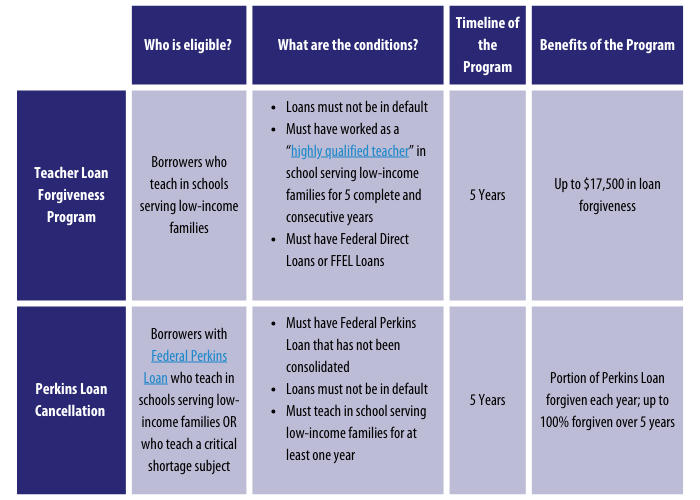

Teachers who work in low-income areas for five full, consecutive years are eligible for the federal Teacher Loan Forgiveness Program (TLFP). Under this program, borrowers can receive up to $17,500 in loan forgiveness. (Note that teachers cannot receive credit for the TLFP and PSLF program during overlapping years–i.e., the five years of teaching that qualify them for the TLFP cannot be counted towards the years that qualify them for the PSLF program.*) As with income-driven repayment plans, the TLFP and PSLF programs appear to be underutilized, as only 16.5% of our survey respondents who took out loans report that they participate(d) in one of these programs.

The Federal Perkins Loan Program ended in 2017, but teachers who have an outstanding balance on these types of loans may be eligible for Perkins Loan Cancellation. Under this program, teachers who work in schools serving low-income students or who teach critical shortage subjects can apply to have a portion of their Perkins loan forgiven each year. If they participate in the program for five years, the full amount of their Perkins loan will be forgiven.

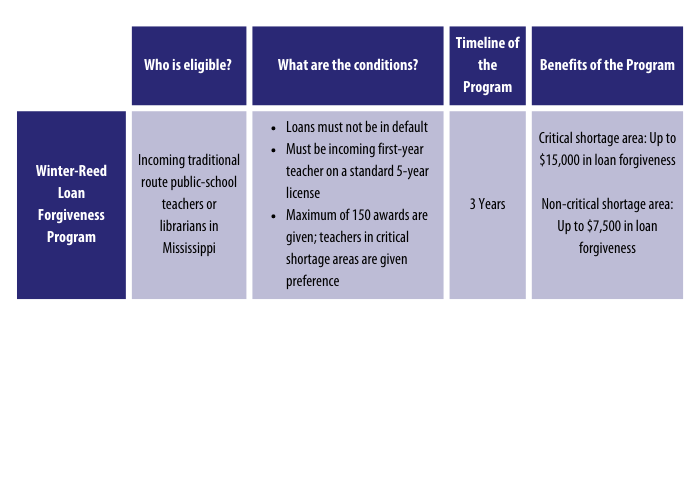

The Winter-Reed Teacher Loan Repayment Program is specific to Mississippi and is an option for certain borrowers who are entering the teaching profession. Through this program, incoming traditional route teachers in critical shortage areas (CSAs) can receive up to $15,000 in loan forgiveness over the course of three years; teachers in non-critical shortage areas can receive up to $7,500. There is an annual cap of 150 participants for this program. Applicants are chosen on a first-come, first-served basis with teachers in CSAs receiving priority.

Teacher Loan Forgiveness Program: “highly-qualified teachers“

Source: PSLF Limited Waiver

Inside Biden’s Proposed Changes

In August, President Joe Biden announced his long-awaited plans for addressing the country’s student debt crisis. While much attention has focused on federal loan forgiveness—$20,000 for Pell Grant recipients and $10,000 for other recipients—other proposals in the plan having to do with income-driven repayment plans and the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program may have an even greater impact for certain borrowers.

One proposal in the plan calls for income-driven repayment plans to be capped at 5% of an individual’s discretionary income, rather than the current cap of 10%. Additionally, a smaller amount of the borrower’s income would be considered discretionary, which would further reduce their monthly payment. Going back to the example above, the borrower who graduated from Mississippi State would have a federal loan payment of almost $500 on a standard plan, and around $200 on a current income-driven repayment plan. Under the proposed plan, her monthly payment on federal loans would be around $60. The plan also calls for the government to cover any monthly interest that remains after a borrower makes their monthly payment on an income-driven repayment plan. While this already occurs on some types of income-driven repayment plans, the proposal would expand the types that are included, preventing loan interest from causing a borrower’s amount of debt to grow over time.

Another facet of the recent proposal has to do with improving the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. Historically, the program has earned a reputation of having muddled guidelines and being stringent in who is approved to receive loan forgiveness. Over the past year, however, the Biden administration has attempted to mitigate these issues with the program through temporarily loosening some of the program requirements. Under the recent student loan proposal, some of these changes to the program would become permanent.

Future of Student Debt Among Teachers

Across the country, there is a growing recognition about the student debt crisis created by the exorbitant–and increasing–costs of college. The crisis is especially acute for teachers, given their relatively low incomes: according to the Education Policy Institute, teachers in Mississippi have salaries that are an average of 14.7% lower than similarly educated workers in the state. The lack of clear information around student loans makes it difficult to tease out the options that borrowers have in paying off their debts. But digging into information on the federal loan system reveals that there are indeed options to lighten the financial burden that student loans pose on borrowers. Teachers have a particularly wide array of resources, including income-driven repayment plans, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, the Teacher Loan Forgiveness Program, Perkins Loan Forgiveness, and–for incoming teachers in Mississippi–the Winter-Reed Teacher Loan Repayment Program.

The coming months and years will begin to reveal the impact of President Biden’s student debt proposals on borrowers. While these will certainly not produce a perfect system, they will hopefully contribute to a more amenable framework for borrowers in Mississippi–especially those who are, or wish to become, teachers. At the minimum, the dialogue spurred by the proposals will be productive in shaping a future system that works better and offers more options to student borrowers.

1 In contrast, compound interest loans are structured so that the principal increases daily by the amount of unpaid interest. We will not go into detail about compound interest loans in this post since they are less common among student borrowers. However, these loans can easily trap students into a cycle of never-ending debt.