Editor’s Note: This is the first part of a two-part series on the Literacy Based Promotion Act.

***

By Grace Breazeale I K-12 Policy Associate

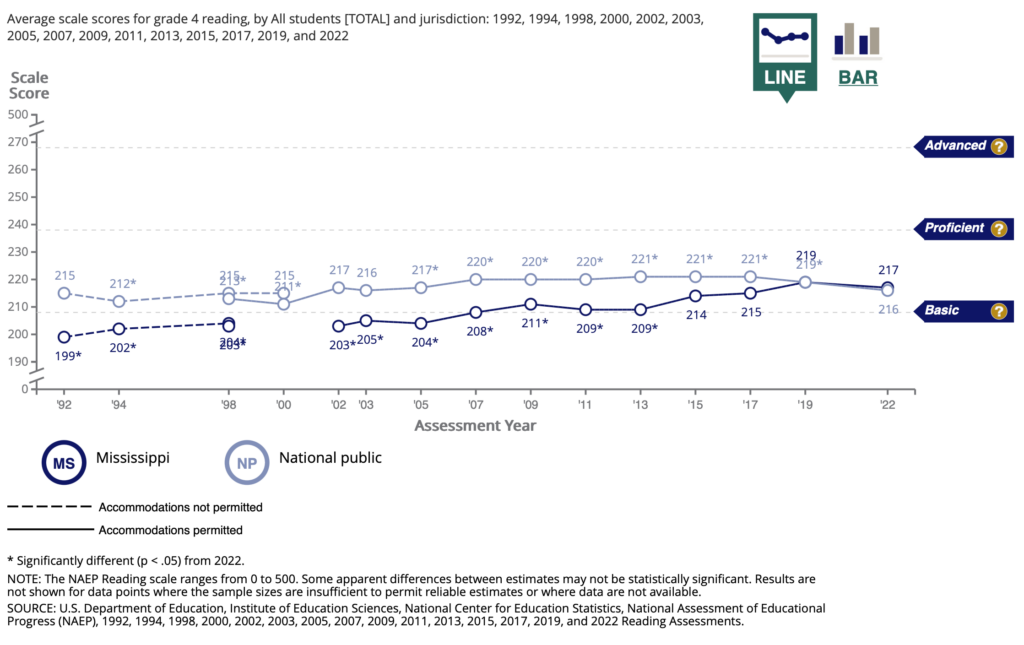

Between 2013 and 2019, fourth grade reading scores on the nationwide NAEP test increased by ten points in Mississippi–a larger increase than in any other state during this time period. In 2019, Mississippi’s fourth grade NAEP reading score was statistically equal to the national average for the first time. It remained equal to the national average during the following testing cycle in 2022, despite disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic. Mississippi’s literacy success is rightfully being recognized as a model for the rest of the country, with other states looking to Mississippi as they consider changing their own approaches to elementary school literacy.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics

The state’s rise in literacy rates was a legitimate accomplishment, with almost every single school district experiencing significant improvement in third grade reading proficiency between 2016 and 2019.

Following the pandemic, however, there was wide variability in improvement between school districts. This vital element of the story is lost when statewide averages make up the sole basis of analysis, as they do in most of the coverage we have seen. In this post, we will draw attention to the variation in improvement. We follow up with an additional post examining several potential drivers behind this variation. This level of analysis will provide important lessons for Mississippi and states that seek to replicate its success.

Components of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act

The Literacy-Based Promotion Act played a large role in Mississippi’s success over the past decade. Passed in 2013, the act took a comprehensive approach to improving reading scores in all corners of the state. The original version of the LBPA encompassed several key components, each with distinct timelines for implementation. Some provisions took effect in the immediate school year following the law’s passage, while others took effect in later years. Below, we outline significant components of the LBPA.

Initial Law

The original version of the LBPA accomplished the following:

- Established the Mississippi Reading Panel to provide guidance in implementation of the law.

- Deployed literacy coaches to low-performing schools, where they provided guidance and support to teachers of early grades.

- Required schools to administer univeral screening assessments in kindergarten through third grade to measure students’ progress and identify students with reading deficiencies. Students with identified deficiencies are given intensive interventions.

- Required schools to communicate with parents of kindergarten through third grade students and inform them of the state’s promotion requirements, as well as making them aware of any literacy deficiencies their student may have and providing updates on their student’s progress.

- Required most third grade students who did not attain a score of two or above (out of five) on an end-of-course reading test to repeat the third grade. Exceptions to this requirement included students who qualified for a “good cause exemption.”

- Required schools to provide intensive reading interventions for students who have been retained, including at least 90 minutes per day of “scientifically research-based reading instruction,” and to provide parents of these students with a “Read at Home” plan.

In January 2014, the MDE also began to offer and encourage teachers to complete Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training, a professional course that equips teachers with knowledge about effective literacy instruction. Teachers in low-performing schools were required to complete this training.

Most provisions of the LBPA were rolled out during the 2013-2014 school year, with the exception of requiring students to pass an end-of-course reading test, which took effect during the 2014-2015 school year.

Amendments to Law and Related Policy Actions

The state legislature amended the LBPA in 2016. The most significant changes are outlined below.

- Raised the threshold that third grade students needed to meet in order to be promoted to the fourth grade: students now need to score three out of five (the previous threshold was two out of five). The law required the increase to take effect in the 2018-2019 school year.

- Required districts to create Individual Reading Plans (IRPs) for students with reading deficiencies. These IRPs were required to include the student’s diagnosed skill deficiencies, their benchmarks for growth, how progress would be monitored over time, the types of interventions they would receive, the types of instructional programming the teacher would use, strategies the parents would be encouraged to use, and any other services that would be provided to assist the student.

Though not a part of the amended law, in 2016 the State Board of Education also began requiring elementary education candidates in Educator Preparation Programs (EPPs) to pass the Foundations of Reading assessment, testing their knowledge of best practices in literacy education, in order to become endorsed in elementary education.

Impact of Pandemic

As in almost every other area of education, the pandemic’s impact on third grade literacy was immense. Schools switched to a virtual format in spring 2020, and end-of-year assessments were canceled, including the state’s third grade literacy test. All third graders meeting other district requirements were promoted to the fourth grade.

During the 2020-2021 school year, some districts continued to implement a virtual format, while others implemented an in-person format or hybrid format. Though students were tested at the end of the school year, test-based promotion requirements were still suspended. Again, students meeting other district requirements were promoted to the next grade level. It was not until the 2021-2022 school year the third graders were again beholden to the test requirements of the LBPA for promotion.

Summary of Milestones

The components of the state’s literacy milestones over the past decade and their different timelines can be confusing. For clarity, the events described in this section are laid out in the timeline below.

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Mississippi Legislature passes the Literacy-Based Promotion Act. Literacy coaches are deployed to schools for the 2013-2014 school year. Mississippi Reading Panel is established. Parent communication requirements go into effect. | First cohort of teachers begins LETRS Training. | Retention policy goes into effect: students who do not receive 2 or above on third grade reading test at the end of the 2014-2015 school year are retained. | LBPA is amended to include individual reading plan (to take effect in 2016-2017 school year) and to increase threshold to pass exam (to take effect in 2018-2019 school year). SBE requires elementary education candidates to pass Foundations of Reading exam. |

| 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Increased threshold for third grade promotion goes into effect for the 2018-2019 school year. | In March, most schools move to virtual instruction for the remainder of the school year. End-of-year assessments are canceled for the 2019-2020 school year. At the end of summer, most schools open in-person, some open hybrid, and some open fully virtually. | End-of-year assessments are administered for the first time since 2019, though retention policies are paused. | End-of-year assessments administered and retention policies put back in place. |

The state’s multifaceted approach to improving literacy proved successful: in the years leading up to 2019, third grade reading scores increased in almost every school district throughout the state. In the following section, we will explore this overall rise, as well as changes on a district level. We will then examine the complicated narrative around literacy achievement that emerged in the wake of the pandemic.

Rise in Reading Scores: 2016 to 2019

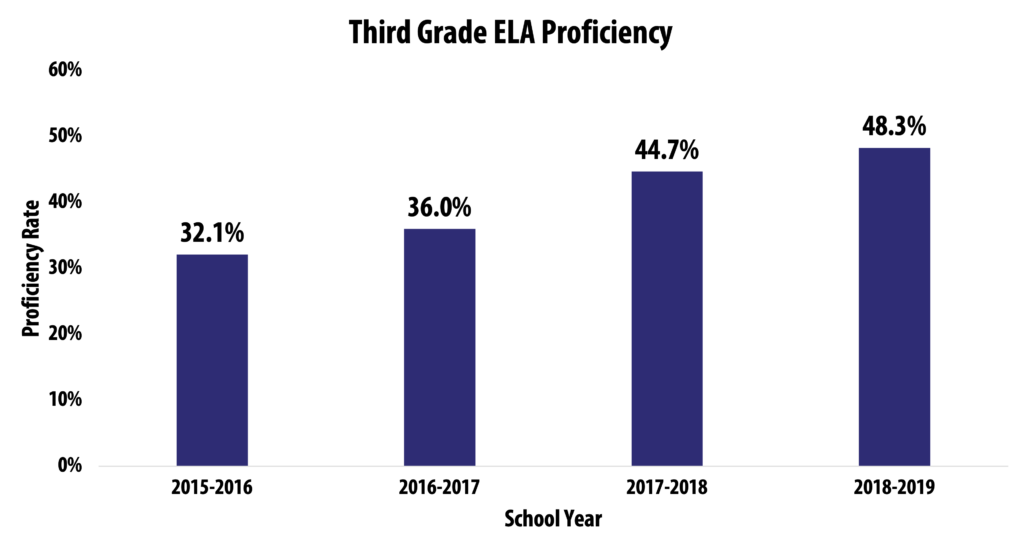

Now that we have established an understanding of the key milestones in the LBPA, let’s look at the impact the law had statewide and on an individual district level prior to the pandemic. To do this, we will examine changes in third grade literacy achievement between the 2015-2016 and 2018-2019 school years.

We chose the 2015-2016 school year as the initial year in our analysis for comparison purposes, as this was the first year that the current standardized test, the MAAP test, was implemented. Additionally, 2016 was one of the last years before the LBPA was implemented in its full form: the act was amended in 2016 to include Individual Reading Plans (IRPs) for students with reading deficiencies (taking effect during the 2017-2018 school year), and to increase the pass score for third graders (taking effect during the 2018-2019 school year).

Mirroring the rise in NAEP scores that we demonstrated at the beginning of this post, the percentage of third grade students scoring proficient in reading on the state test increased dramatically. Overall, proficiency improved from 32.1% to 48.3% between 2016 and 2019–an increase of 16.2 percentage points.

An average rise in scores, however, does not necessarily imply equal improvement in all districts across the state. To determine whether the law was effective in districts of varying characteristics and with varying amounts of resources, we examined the changes in proficiency throughout each district in the state. In total, a remarkable 97.1% of districts improved their scores between 2016 and 2019, with improvements ranging from 0.2 to 35.1 percentage points. Improvements in most districts were large: of districts that increased their scores, 81.3% improved by more than 10 percentage points. Scores fell in 2.9% of districts, with declines ranging from 0.5 to 9.3 percentage points.

The vast majority of districts showing improvement speaks to the effectiveness of the LBPA at targeting all districts, regardless of location.

Variation in Recovery: 2020 to 2023

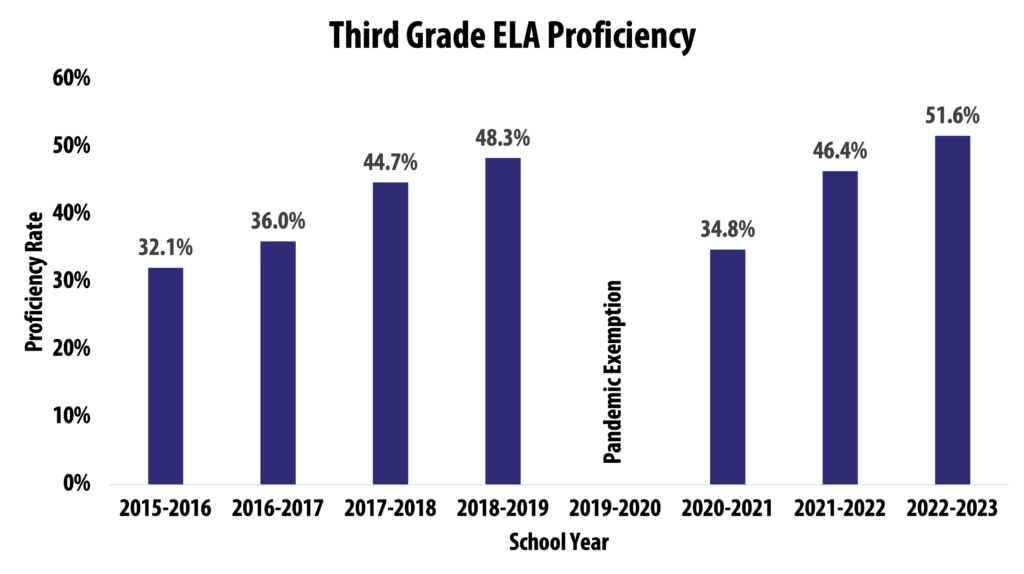

In the aftermath of the pandemic, there was widespread concern that students would struggle to bounce back from pandemic-era setbacks. It was welcomed news when third grade ELA MAAP proficiency scores exceeded their pre-pandemic levels in 2023.

While the above trends indicate that Mississippi has recovered from the impacts of the pandemic–at least in the realm of third grade literacy–district-level data adds some nuance to this trend.

Some districts have returned to their pre-pandemic ELA proficiency levels, but many have not reached this milestone. In fact, 54 (37.0%) of school districts have thus far been unable to exceed the level of achievement they attained prior to pandemic disruptions, with deficits ranging from 0.5 to 23 percentage points. Of these districts, 23.5% are more than 10 percentage points behind their pre-pandemic scores.

The statewide average scores may indicate recovery, but these averages can only go so far in capturing the wide variation in experiences of the 440,000+ students served by the state’s public school system. While some districts are exceeding their pre-pandemic achievement, many appear to be having a difficult time bouncing back from the pandemic.

In the second part of this series, to be released next month, we will explore potential factors related to this variation in recovery.